Today’s question comes from Charly F, and it’s a good one. Q: What might you fish on the Farmington during January to March with no real hatches going on?

A: Let’s start with the hatches. There are times during the winter when there’s plenty going on hatch-wise. We don’t have the glamour mayfly hatches, but midges hatch year-round, and are a primary food source. You won’t see trout splashing on the surface like you will during a June Sulphur emergence, bit it is possible to find trout sipping midges or W/S Caddis (a hatch that is sadly on a downward slope) or early stones on the surface or in the film. It should be also noted that March is very different from January and February. But that’s an entirely different article!

If the question is, what does Steve Culton fish on the Farmington in the winter, I can be more specific. I used to do some winter dry fly fishing on the Farmington, but for various reasons I’ve cut back on that. (If I saw fish actively feeding on the surface, I would not hesitate to go the dry fly route.) Most of my winter fishing is nymphing or streamers. The method I choose depends on conditions and what I feel like doing on that day or hour. Much of what is hatching or available to trout in the winter is small. So if I’m nymphing, we’re talking a point fly no bigger than a #14 (like this Frenchie variant) and a dropper above it that’s a #18 or smaller, like a Starling and Herl. That gives me a mayfly/caddis nymph and a something midgey to show the trout. I’m less hung up on patterns than I am presentation: the best winter nymphs are often the ones that are presented at a dead-drift along the bottom in a trout’s feeding lane.

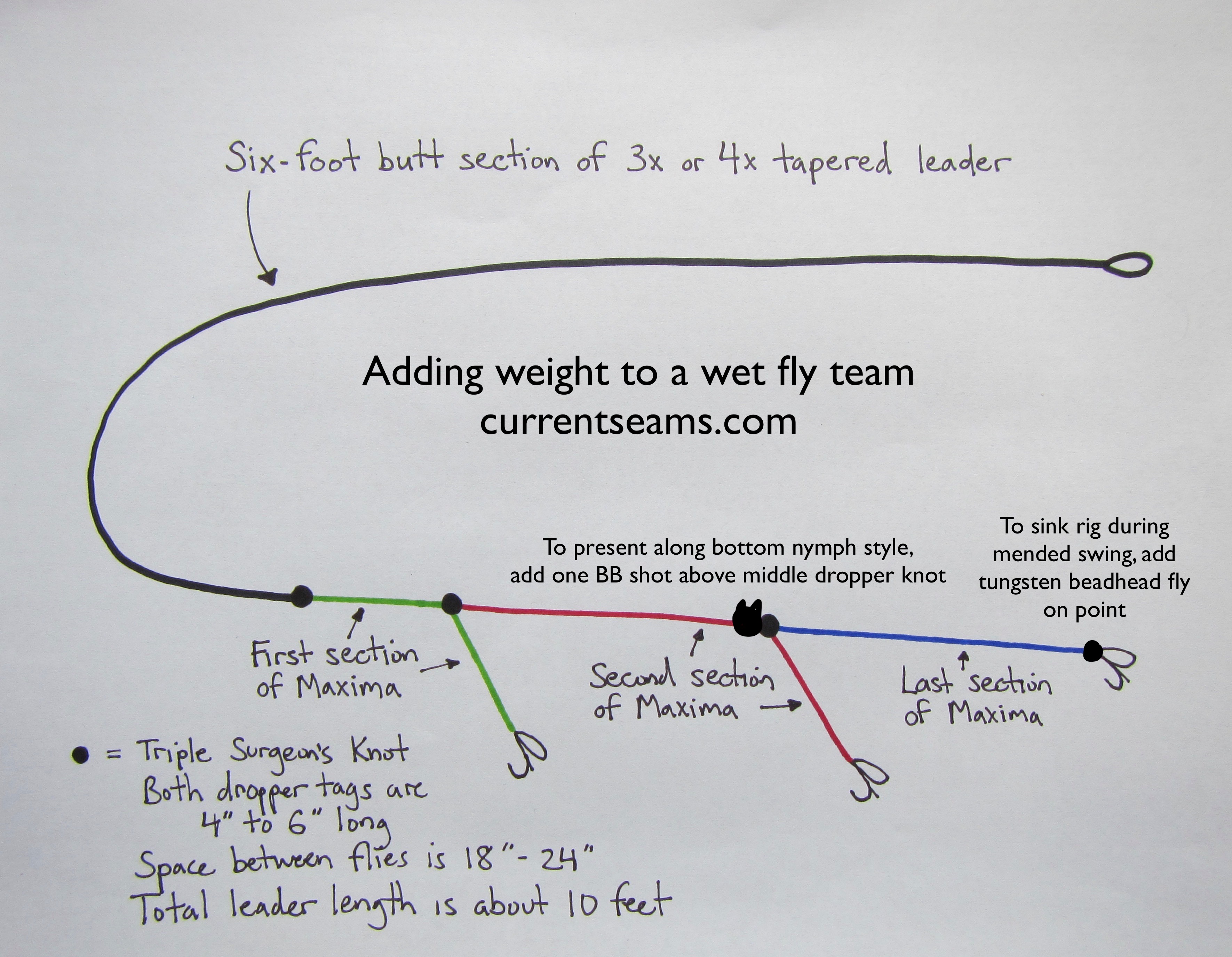

Streamers are a different animal. You’ve got to be willing to accept blanks in the winter. But if the streamer bite is on, you’re going to have fun. I tend to favor core patterns like Coffey’s Sparkle Minnow or my Deep Threat. I don’t go bonkers trying to find a magic color. As with nymphing, presentation matters. I may simply do mended swings. I may go for depth with an integrated sink tip line, weighted fly, and then a slow retrieve. I may do both. What is paramount is that I cover water. I’m looking for that one trout that has a protein payoff in mind.

What’s important to note is that the winter bite can be notoriously fickle. Some days, it doesn’t exist. Other days, it’s 30-45 minute window. Some days (however rare) the feed bag is on from 11am-3pm. Hope that helps!