“Winter Fly Fishing on the Farmington River” first appeared in the February 2015 issue of Mid Atlantic Fly Fishing Guide.

The best part about winter fly fishing on the Farmington is not that on any given day, you have a good chance of catching trout. It’s that on any given day, you have a good chance of catching trout on a dry. Or a wet. Or a nymph. Or a streamer.

A classic tailwater, the West Branch of Connecticut’s Farmington River starts at the Hogback Dam in Barkhamsted, and flows some 60 miles to its confluence with the Connecticut River in Windsor. Between Barkhamsted and Unionville are dozens of miles of blue ribbon trout water, much of it open to anglers year round.

Resident salmonids include brown trout, rainbow trout, brook trout, and juvenile Atlantic salmon. In addition to stocked and holdover fish, there are substantial numbers of stream-born trout and char in the Farmington. (The 2013 DEEP census placed wild fish at 50% of the trout population.) Because the Farmington is a tailwater, it remains cool and trout-friendly in the warm summer months. It also means that during the unforgiving bitterness of winter, the source water is well above freezing. That’s good for trout. Good for hatches. And of course, good for fishing.

Small flies catch big winter browns on the Farmington. This buck was taken on a size 18, 2x short bead-head Pheasant Tail.

~

Winter access and gear

Often, the most challenging part of a winter outing on the Farmington is finding a place to park. Only a handful of lots are plowed. Dirt roads are not plowed, and many are gated until spring. During snowy winters, the pulloffs that line East and West River Roads along the TMA are buried beneath an impenetrable hedge of snow and ice. A four-wheel drive truck with good tires and ground clearance will help you negotiate spots a sedan can’t manage. The river in winter doesn’t draw close to the crowds it sees in summer. Still, on a mild day, popular places like Church Pool are likely to be busy.

If there’s an extended cold snap, some of the slower pools will build up shelf ice along the shore. Never attempt to walk across shelf ice to get into the water. While I like to target days when the mercury is above thirty-two degrees, be aware that runoff generated by some of the warmer thaws can send water temperatures plummeting. Extended periods of consistent weather often mean good winter fishing. Conversely, a sudden cold snap is usually bad for business.

Dressing for winter fishing is a matter of common sense: know the weather forecast, and know your body’s limitations. I tend to run cold, so my best friend is my 1,000 grain insulated boot foot 5-millimeter neoprene waders. Breathable layers and hand and toe warmers are essential gear. I highly recommend studded boots and a wading staff – falling in the river is never fun, even less so in January. Remember to get out of the water and walk around for a few minutes every hour to avoid frozen leg/feet syndrome.

An angler patiently waits for risers on a cold February morning.

~

Winter Dry Fly Fishing

Just because there’s snow on the ground – or in the air – doesn’t mean you won’t find a pool that’s simmering with rise rings. The Farmington River has a fairly consistent winter midge hatch. Some of those midges push the size 18 envelope, but when planning your fly selection, think small, smaller, smallest. The tiny blue-winged olives (size 22-28) of late fall often carry over into December. But the real hero hatch for winter dry fly aficionados is Dolophilodes distinctus, the Winter/Summer Caddis.

In the winter, I don’t usually arrive on the river much before 11am. An exception is the W/S Caddis hatch, which is usually an early morning event. Distinctus is appropriately named. They rise to the surface as pupae, size 18-24, then scoot across the water to the shore where they complete their emergence. During this scooting phase, they are highly vulnerable to feeding trout.

This W/S Caddis Pupa pattern is a favorite of Farmington River dry fly anglers. So simple: dark grey foam body and dark dun hackle, size 18-24.

The trout will always tell you how they want the fly presented during a W/S Caddis hatch. Hedge your bets by targeting actively feeding fish. If you’re not getting any takes with a classic drag-free drift, try going down a size or two. If that doesn’t produce, try waking the fly, replicating the pupal dash across the surface. Sometimes that movement is the feeding trigger.

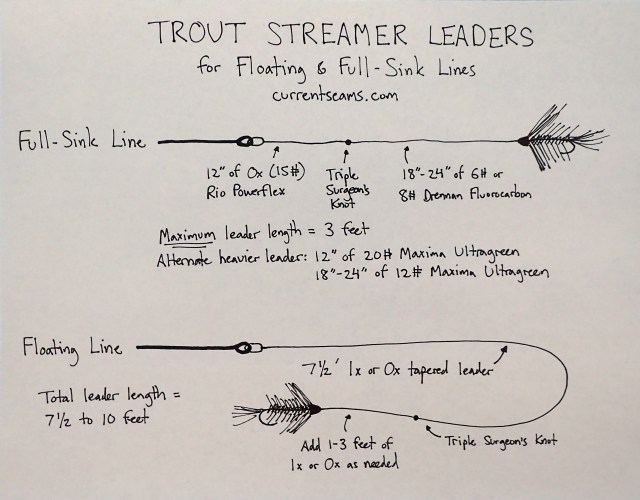

Winter Streamer Fishing

For years, I never considered fishing a streamer on the Farmington in the winter. Then, one January day, I saw a spin angler take trout after trout on a small jig-head soft plastic. I returned to the pool he was fishing the next afternoon with a full sink (7ips) integrated line and a tungsten cone-head streamer. Needless to say, I went home happy, and now there are days when I am committed solely to the streamer cause.

Deep, dark pools with water moving at a walking pace or slower are the first places I’ll start. Getting the streamer down, and a slow-to-moderate retrieve have produced the best results for me. I stay out of the faster runs, although I sometimes do find willing customers in the transition water at the heads of pools. In shallower runs, I like to let the streamer swing and dangle like a wet fly before I begin my retrieve.

Winter Nymphing/Wet Fly Fishing

Swinging a team of wets through the current seams of a boulder field is a sound spring, summer, and fall strategy. But as the winter cold slows trout metabolism, the dead drift in slower, deeper waters – and the seductive upward swing of the flies – becomes the higher percentage subsurface play. That’s why I like to fish a nymph and a wet on my two-fly indicator setup.

Two flies give the trout a choice: color, size, species, and life stages. Because what is hatching this time of year is typically small, I like at least one of the flies to be in the 18-20 range. Eggs and attractor nymphs certainly work, but I prefer to stick with more natural colors and patterns. Don’t be afraid to include larger (6-12) stonefly patterns in the mix. Because the soft-hackled fly straddles the line between nymph and emerger, I’ll rig that fly higher on the leader so it will always be closer to the surface than the nymph. Keep it simple. A soft-hackled Pheasant Tail or Hare’s Ear will serve you well.

I’m a big fan of indicator nymphing in the winter for two reasons. One, it lets me cover more water. Two, the takes of winter trout can be nearly imperceptible. Sometimes those micro-twitches, shudders, or stalls are the only sign of the take. Look for a reason to set the hook on every drift. As you complete the dead drift phase of your presentation, let the flies swing up. If an emergence is taking place, aggressive feeders will often chase and strike.

An exquisitely parr-marked wild Farmington brown that chased a nymph on the upward swing.

Where to fish

The Farmington River Anglers Association (fraa.org) has updated its popular book A Guide to Fishing The Farmington River. The guide includes comprehensive river maps and pool descriptions. For daily reports, weather, and water flows, visit UpCountry Sportfishing at farmingtonriver.com.