This piece first appeared in the May 2014 issue of Mid Atlantic Fly Fishing Guide. Many thanks to MAFFG for allowing me to share it on currentseams.

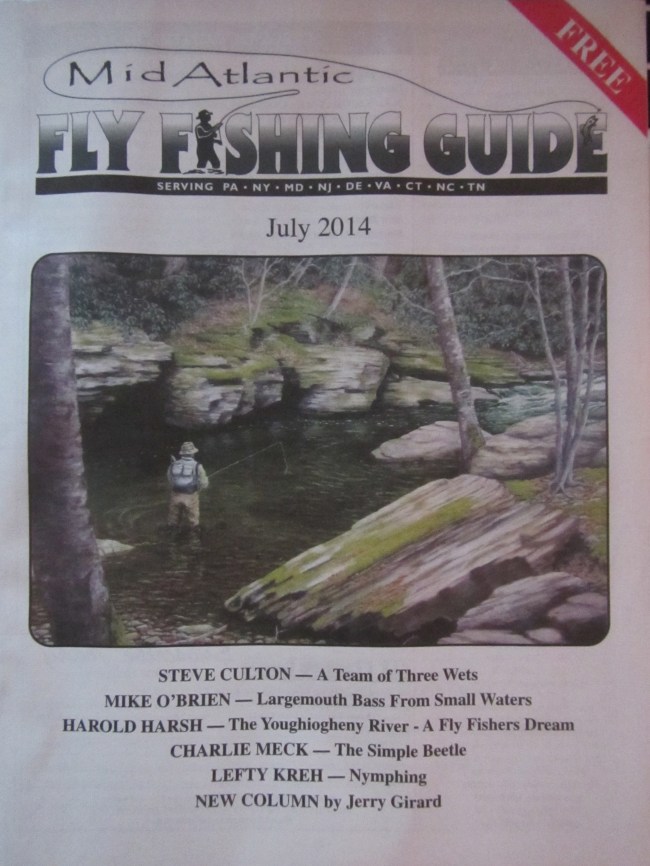

It all started with a bushy dry – an Elk Hair Caddis – that I was presenting upstream. I was fishing one of my favorite thin blue lines, a high-gradient brook nestled deep in the Appalachian foothills. “Brook” may be too generous a word; it’s more of a connected series of waterfalls than anything else.

For years, I had been fishing this exquisite gem with dry flies, always moving upstream, casting into the white water at the head of its plunges. While I’d had a few takers on this day, the brookies weren’t throwing themselves at the dry with their usual fervor. Of course, in unspoiled waters such as this, catching is secondary to simply being there. But on my return down the trail, curiosity got the better of me.

Surely, I reasoned, there were char in the pools where I blanked. Maybe they were just bashful about showing themselves on the surface. A quick rummage through my fly box produced a bead-head micro-bugger, about a size 14. The fly had barely settled beneath the surface when it was set upon by a band of shadowy marauders. Clearly, I was on to something.

The science behind the subsurface magic.

Small stream wild brook trout aren’t renowned for their selectivity. In streams where significant, regular hatches may be a luxury, highly opportunistic feeding habits are crucial for survival. But survival isn’t solely about eating. It’s also about limiting exposure to predators. Every time a brookie rises to the surface, it becomes a target for birds and mammals. Bigger fish are older fish, and older fish get that way by minimizing their chances of getting eaten.

Water level plays a significant role in how you decide to fish a brook. Many small streams are dependent on rainfall to supplement their flows. During extended periods of low water, wild fish settle into survival mode. They keep activity to a minimum, especially in daylight. You may not see them, but they’re there, hunkered down along the bottom, beneath deadfall, submerged ledges, and undercut banks. Good luck getting these ultra-cautious, spooky fish to rise to a dry. But, a submerged fly is an entirely different matter. Even the wariest trout finds it difficult to resist the temptation of a meal drifting past at eye level.

High or deep water also presents a unique set of challenges. Some of the plunge pools I fish are overhead deep, even during normal flows. Trying to coax a brook trout to move six feet to the surface to take a dry is not a high percentage play. Use a weighted soft-hackle to shift the odds in your favor. James Leisenring encouraged anglers to fish their fly “so that it becomes deadly at the point where the trout is most likely to take his food.” Translation: fish beneath the surface. Make it easier for the brookies to eat.

What’s more, brook trout are highly curious creatures. They are eager to investigate new arrivals to their world, especially if it poses no threat, looks alive, and seems like it might be something good to eat. Just as it happened that first time I fished a deep wet, I find that brookies will race each other to take the fly. Often, the competition doesn’t end until the last char has been hooked.

Presenting the downstream wet.

I like to position myself in front of the head of the pool I’m fishing; that often means I’m standing in the tailout of the pool above, along its banks, or on the rocks that create the waterfall (if there is one). Stealth is a matter of conditions and experience. Some pools have a deep holding run with a lane of whitewater or a riffly, mottled surface; in these, you can take a more cavalier approach. Others demand that you channel your inner commando, crouching, crawling, or hiding behind saplings and boulders to get into casting position.

In a plunge pool, I’ll begin by jigging my fly into the whitewater. Delivering the fly can hardly be called a cast; I’m simply dunking it and manipulating the rod tip with an up-and-down motion. If I don’t get a strike – and I’m always surprised when I don’t – I’ll strip out a few feet of line and repeat the process a little farther downstream.

Shallower runs invite you experiment with classic presentations such as the wet fly swing or the mended swing. With the former, you’re making a quartering cast down, then letting the fly swing across and up toward the surface. To slow the speed of the fly as it swings, simply add a few upstream mends.

Letting a soft-hackled wet fly hold in the current downstream – also known as the dangle – is almost never a bad idea on a small stream. As the hackles flutter in the current, they whisper to the brookies, “I’m alive.” By all means, add to the illusion of life with short, pulsing strips, or by drawing the fly toward you, then letting it fall back in the current.

Three proven small stream wets.

In the warmer months, terrestrials are a major component of the small stream trout’s diet. The Starling and Herl is an old English pattern that makes a fine imitation of an ant, a beetle, or even a dark caddis or stonefly.

~

Thread: White

Tail: Short marabou wisps over pearl Krystal flash

Body: Small white chenille, ribbed with pearl flash, palmered with soft white hen

I’ve made several strategic changes to the classic Woolly Bugger template. The tail is shorter and sparser, which cuts down on nips away from the hook point. The hackle and collar is soft hen. And with a tungsten head and wire underbody, this fly sinks like a stone, causing it to rise and fall like a jig when you strip it.